Sites of Shaping and Change

How Social Contexts Influence Our Senses (and the other way around)

Recently I’ve been looking at how social contexts influence our senses. As a social scientist, this is a go-to for understanding my personal life experience, inside and out, as well as for gaining insights into broader cultural dynamics.

As a queer woman of color, when I walk down the street in a new city, or even in a new neighborhood in the city where I live, all of my cells become activated. It happens automatically and almost imperceptibly. Whether or not I am conscious of it, my body is scanning my environment, assessing whether I am safe, or whether there is any danger or threat. Is it safe to hold my partner’s hand? What do the people around me look like? What is their body language?

As a professional, whenever I enter a gathering of a new group of colleagues, all of my senses are also taking in the room. It matters whether this group is a room full of strangers, or a trusted circle of teammates that I have been working with for years. Although I am not a zebra on the savanna, scanning the horizon for lions, nonetheless my body is still automatically and unconsciously making a mental model of the environment and assessing safety, connection, danger, and threat. This is a primal, evolutionary function.

As I previously discussed in my Substack post “Feeling Our Bodies and Our Emotions: Interoception, the 8th Sense”, the processes of interoception, which give rise to the internal sense of the physiological state of the body, are happening all the time and are a basic characteristic of human experience.

We often act as if this bag of bones, sinews, and blood that make up this mortal coil is independent from everything else around it. In the blinding rush of 21st century life, we can forget that this human form exists within social contexts. Our bodies, and therefore our interoception, are influenced by the social landscape. In turn, our bodies can also influence the social landscape around us.

Ask any woman, BIPOC, LGBTQIA+ person, or anyone who has suffered trauma. The scenario described above, of walking down the street in a new place, scanning the environment for danger, is an all too familiar one. In fact, when you grow up in those bodies, the neural pathways are so deeply wired to do this that it’s spontaneous; it’s a quintessential example of how the biological processes of interoception are shaped by our social contexts.

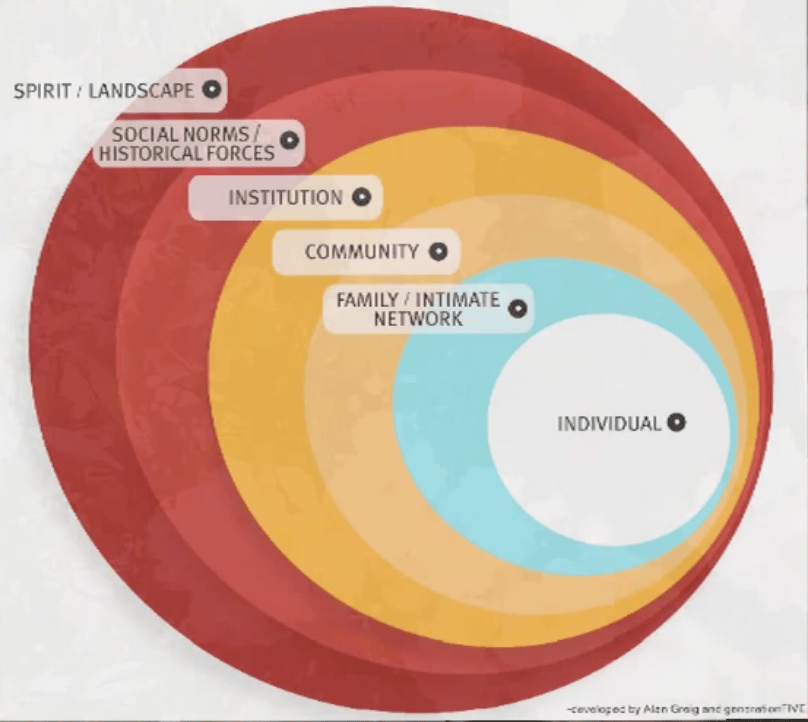

Looking at the concentric circles in the diagram above–referred to by practitioners of somatics such as Strozzi Institute and generative somatics as “Sites of Shaping, Sites of Change”–we find one useful way of understanding the complexity of these social contexts. Social norms are transmitted to us, and reinforced, at each Site. How we embody our beliefs, strategies for surviving and thriving habits, and actions, are developed as we interact with the experience of life in our world. We adapt to our experiences and our environments–whether for survival or resilience–in our thoughts and in our bodies, which then become automatic and “normal.” (See below for resources to learn more.)

In my case for example, I am a first-generation immigrant, born in the Philippines, who came to the United States when I was a year old. Like other BIPOC people and immigrants, I have experienced xenophobic and racist microaggressions, and outright threats, due to my physical appearance, name, or other markers. As a queer person, I exist in a homophobic society where hate crimes against LGBTQIA+ people are a feature of the landscape.

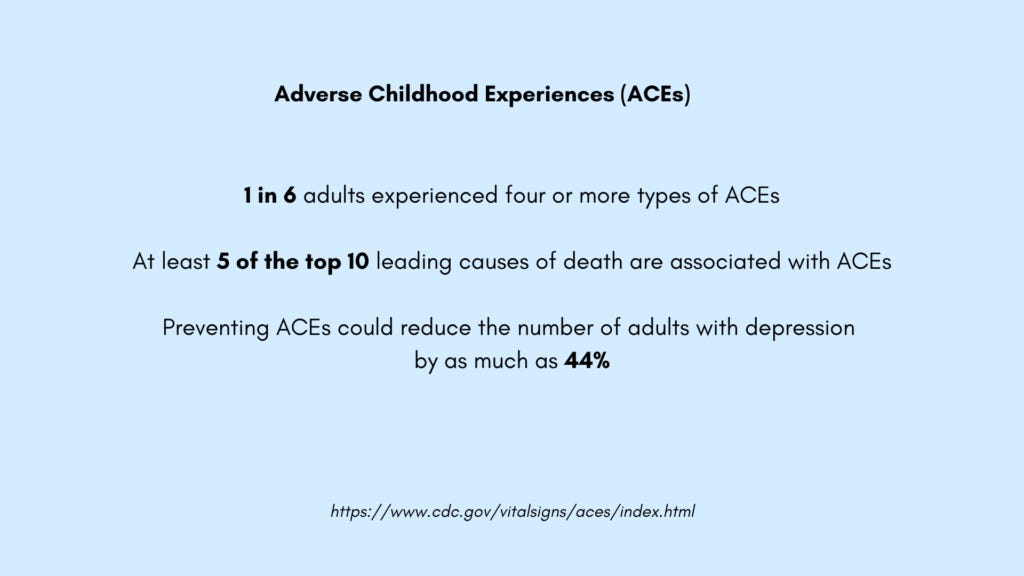

We hear about how Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) adversely shape the neural pathways of children, attuning their systems to threat and putting their nervous systems into an elevated, prolonged state of toxic stress. For children who live under multiple threats from ACES (e.g. domestic violence, caregivers with mental health issues or drug addiction, poverty), the growth and development of their neurological system is negatively impacted, sometimes stunted, with effects on physical and mental health lasting well into adulthood.

And yet, science also reminds us of two of the biggest leverage points we have: neuroplasticity and emotional resilience.

Neuroplasticity refers to the fundamental ability of the brain to change, i.e. for the neurons to make new pathways and connections, in response to new stimuli. It’s just a fancy way of saying that our brains have the ability to transform throughout life, not just when we are children, but throughout our lives. This is very good news.

Emotional resilience is our natural ability to “bounce back” from adversities and challenges in life, and come back into a sense of balance. I like to think of resilience not just as coming back to a baseline of “okayness” but to grow, thrive, and flourish even more, what some are calling post-traumatic growth.

For example, the biggest factor in helping children experiencing ACES is the presence of at least one caring adult, who can function as a buffer. Just one caring adult can give the child’s developing nervous system some experience of calming, regulation, and secure attachment. This has been shown time and time again to mitigate the negative effects of ACES, and help the child’s neural system to create healthier pathways.

In my own life, I’ve worked hard to cultivate a variety of communities for myself–whether my Buddhist sangha, the intentional community where I live, chosen family of LGBTQIA+ folks, families of color, etc.–where I can feel safer and more connected. In these groups, I can palpably feel my body shifting into a more relaxed, less activated state. Because of neuroplasticity, every moment I spend in these spaces also shapes my neural pathways and my overall sense of well-being. Community is one of the biggest resources, therefore, for emotional resilience.

We are mammals. We are built this way.

***

The “Emotional Rescue: Burnout to Resilience” Coaching Program empowers us, as individuals and in community, to work with our embodied experience to prevent burnout and build emotional resilience.

***

Musical Inspiration

**

To Learn More

This “Sites of Shaping, Sites of Change” model is based on a public health framework developed by Alan Greig and generationFIVE. It is further elaborated in the work of Staci K. Haines and generative somatics. Video:

The Politics of Trauma: Somatics, Healing, and Social Justice

How to Nourish Your Resilience in a Time of Trauma

Generative Somatics: www.generativesomatics.org

Adverse Childhood Experiences

For a compelling, and personal, explanation of ACES, learn from Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, Surgeon General of California: Ted Talk: How childhood trauma affects health across a lifetime or read her book, available at your local library (The Deepest Well ) or your independent bookstore: The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity